Ever since human spaceflight took off in 1961, more than 100 female astronauts have lived and worked in microgravity. Scientists have collected a lot of data on impacts of living in space but documentation of the effects on reproductive health, particularly those of women, has been scarce. Scientists at Cornell University’s Carl Sagan Institute are now trying to change that through the AstroCup project.

A team led by astrobiologist Lígia Coelho, a Postdoctoral Fellow in astronomy in the College of Arts and Sciences, is developing methods to give women a choice to menstruate in space during long duration missions to the Moon and Mars.

View this post on Instagram

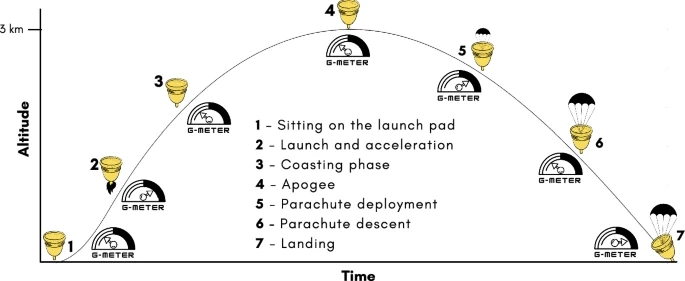

In 2022, the team sent a payload with two menstrual cups on an uncrewed rocket and tested their resilience and functionality under the stresses of spaceflight conditions. The flight lasted nine minutes and the payload reached an altitude of three kilometres, allowing researchers to determine the durability of the cups manufactured by Finland-based company Lunette.

Results of the test

The results of the test conducted on October 15, 2022 were shared in a study published in the journal NJP Women’s Health on December 2 and they look promising. The authors wrote that the two silicone-based menstrual cups survived elevated levels of vibrational loads and mechanical stresses under varied conditions (air pressure, temperature, humidity and linear accelerations).

Their performance was evaluated using water and glycerol, an analog for human blood, and the cups showed no leaks, liquid contamination or material degradation. There were also no signs of wear or tear and their material integrity was consistent with the cups kept on Earth under standard lab conditions for comparison.

“This resilience is critical for space missions, where equipment must endure rigorous conditions. Menstrual cups could be a reliable and sustainable option for managing menstruation during missions to the Moon and Mars,” the authors wrote. “Unlike disposable products, they reduce waste, which is a key advantage in the confined, resource-limited environment of space. This could improve astronauts’ quality of life, autonomy, and simplify logistics for long-term missions.”

The path ahead

The test flight was a huge success but researchers have highlighted that the cups are yet to be tested in microgravity. The Moon has about 1/6th of Earth’s gravity whereas Mars has about 1/3rd. Testing them in similar environments is crucial because reduced gravity might affect how menstrual fluids flow, and gravitational and pressure differences could influence the performance of the cups.

View this post on Instagram

“The success of AstroCup in Earth’s gravity is a positive starting point, but further testing is needed to confirm how the cups perform in reduced gravity,” the authors wrote. “For example, lower gravity might alter fluid dynamics, potentially requiring adjustments to the cups’ design or usage. Simulations in microgravity would help verify their effectiveness for the Moon and Mars.” They’re now planning to expose the cups to space radiation by sending them to the International Space Station (ISS).

The researchers also need to figure out a way to clean such devices effectively because blood could serve as a medium for pathogenic bacteria and impact crew health. Besides, the sanitation process must require minimal use of water.

Menstruation in space

The 2022 test flight was a giant leap toward ensuring women have autonomy in space. Currently, female astronauts prefer supressing their periods using hormonal contraception on 6-months or longer missions to the space station. However, missions to the Moon under NASA’s Artemis Program could last up to a year or even over a decade eventually, and there’s not enough research on impact of chronic hormonal contraception use on astronauts’ health.

According to the authors, a solution is much-needed because female astronauts delay parenthood, on average, by 5.6 years compared to their male colleagues. Letting them choose whether to use contraception or not could allow reproduction in space or colonies on the Moon and even Mars.

“I get passionate about the reasons why menstrual devices are still not in space,” Coelho said in a statement by Cornell University. “We need to have a serious conversation about what it means to have autonomy for health in space.”

Reusable devices like menstrual cups could be game-changer because they would solve the logistical and financial burden of shipping common menstrual products such as pads or tampons to space. NASA reportedly estimates that the cost per pound to launch these single-use products is $10,000. Menstrual underwear could be another alternative for current and future missions but tests are required to determine if they can be repurposed or need adaptations, the authors wrote.

ALSO READ: Artemis 2 Explained: NASA’s First Crewed Moon Mission Since 1972

ALSO READ: Artemis Vs Apollo: Why New Prada Spacesuits Are Better For NASA Astronauts